We are losing the war on drugs. We are spending staggering amounts of money and we can’t build prisons fast enough. We cannot afford to continue throwing money away on ineffective drug enforcement. Politicians all too often begin the process of creating policy by first throwing out all the facts. This must stop.

On June 2nd the Global Commission on Drug Policy released a report[1] detailing their findings.

“The global war on drugs has failed, with devastating consequences for individuals and societies around the world. Fifty years after the initiation of the UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, and 40 years after President Nixon launched the US government’s war on drugs, fundamental reforms in national and global drug control policies are urgently needed.”

The commission’s recommendations are summarized in their press release.

- End the criminalization, marginalization and stigmatization of people who use drugs but who do no harm to others.

- Encourage experimentation by governments with models of legal regulation of drugs (especially cannabis) to undermine the power of organized crime and safeguard the health and security of their citizens.

- Ensure that a variety of treatment modalities are available – including not just methadone and buprenorphine treatment but also the heroin-assisted treatment programs that have proven successful in many European countries and Canada.

- Apply human rights and harm reduction principles and policies both to people who use drugs as well as those involved in the lower ends of illegal drug markets such as farmers, couriers and petty sellers.

But writing in Foreign Affairs[2] Mark Kleiman suggests that both current drug policy and the proposed alternatives will not be effective.

“Current policies, clearly, have unsatisfactory results. But what is to replace them? Neither of the standard alternatives — a more vigorous pursuit of current antidrug efforts or a system of legal availability for currently proscribed drugs — offers much hope. Instead, it is time for Mexico and the United States to consider a set of less conventional approaches.”

He believes that progress demands that we accept our limitations and focus on what can be accomplished.

“If policymakers are willing to adjust their strategies to reflect both the limits of the possible and the relative importance of various goals, then there could be smaller illicit drug markets, less drug-related violence, and fewer people behind bars. Reducing the number of casual drug users should be a far lower priority than reducing the number of criminally active heavy users of hard drugs; decreasing violence is not only more feasible but also more vital than decreasing the flow of drugs.”

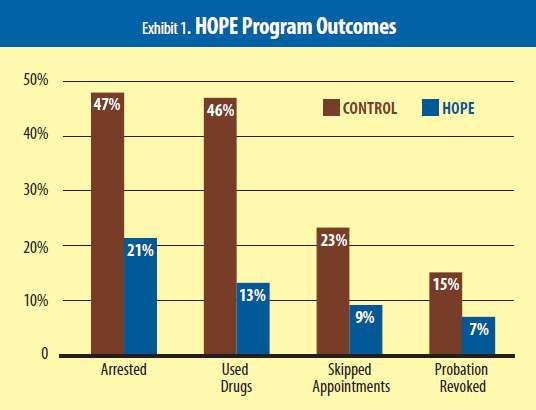

He cites Hawaii’s HOPE program[3] as evidence that such heightened focus on the most serious offenders can be effective.

But he adds a warning that we need to manage our expectations. We cannot win the war on drugs. We cannot make a drug free world.

“Of course, more logical policies cannot guarantee better results, and even a better result would not be a solution to the drug problem. At best, Mexico and the United States could end up with a result that would be, in the words of the economist John Kenneth Galbraith, merely ‘distasteful’ rather than ‘catastrophic.’ But a bad result is preferable to a worse one.”

[1] Global Commission on Drug Policy, “War on Drugs, Report of the Global Commission on Drug Policy”, June 2011

[2] Mark Kleiman, “Surgical Strikes in the Drug Wars, Smarter Policies for Both Sides of the Border”, Foreign Affairs September/October 2011.

[3] The PEW Center on the States, “The Impact of Hawaii’s HOPE Program on Drug Use, Crime and Recidivism”, January 2010

Angela Hawken, Ph.D. and Mark Kleiman, Ph.D. , “Managing Drug Involved Probationers with Swift and Certain Sanctions: Evaluating Hawaii’s HOPE”, December 2009